Judith Leyster and Tormented Cats

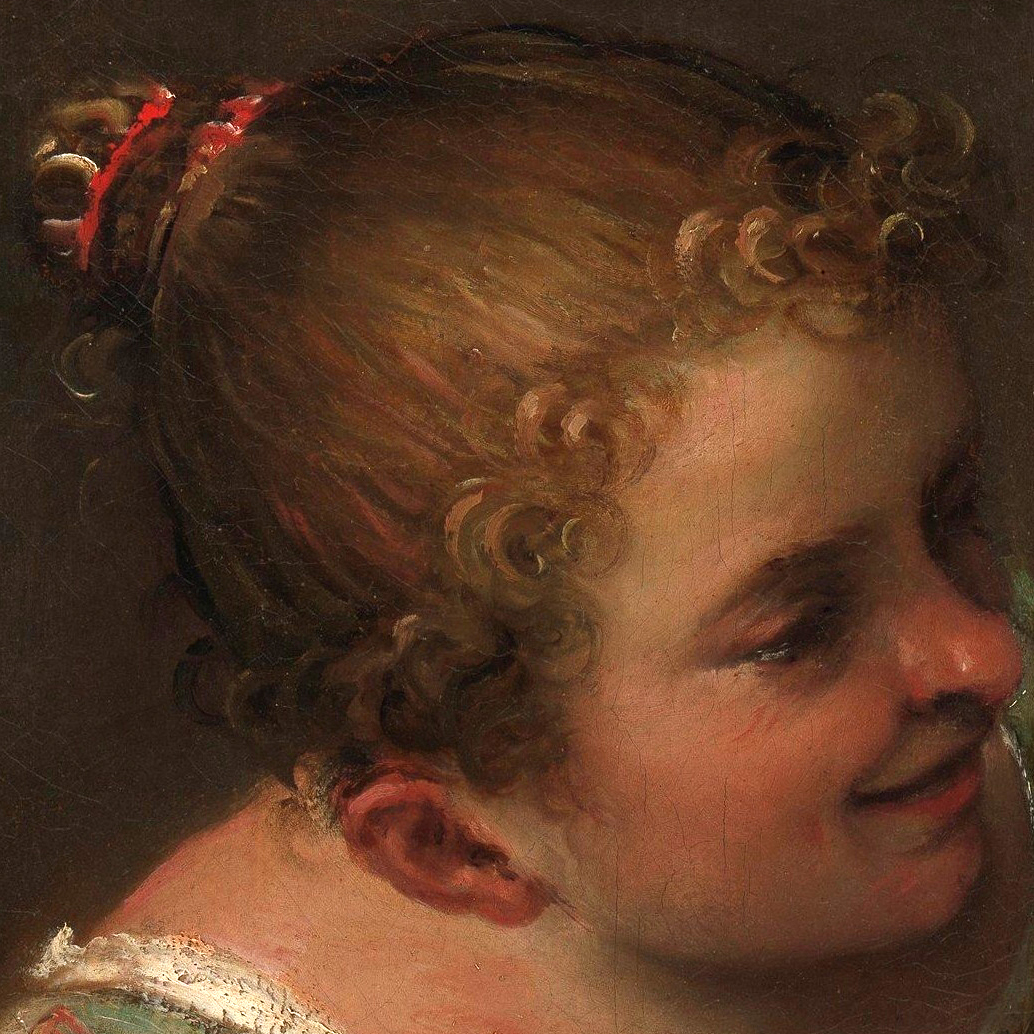

You can see how successful, confident, and talented Judith Leyster (1609 to 1660) was from her self-portrait. For generations people assumed this self- portrait was painted by another Dutch artist - a male artist - Frans Hals. Judith Leyster was lost and forgotten until a museum bought a well-known Frans Hals painting. The museum discovered that someone had forged Frans Hals' signature over hers.

This self-portrait was probably Judith Leyster's "masterpiece." A masterpiece wasn't necessarily an artist's best painting: it was a painting submitted to a guild when applying for master status. It's doubtful she'd ever sat down to paint in such finery. Her lace collar is a symbol of her financial success. She was accepted as a master into Saint Lukes' Guild of Haarlem before she was twenty.

Artwork Attributed to Other Artists

Leyster's paintings were hiding in plain view for over 200 years... more may be discovered in the future. Her paintings were either attributed to Frans Hals or to her artist husband Jan Miense Molenaer. Although the painting sold to the museum was an intentional deception, some confusion over her work is understandable. Frans Hals was one of the better-established painters in the region and put out similar paintings. As for her husband, as a married couple they shared the same studio, props and models. At times, they may have even both worked on the same painting.

The confusion doesn’t end there. I found one painting attributed to her showing a boy holding bread in one hand and a cat in the other. Another painting of two children with a cat is also attributed to her. Does either of these not feel quite right to you?

The dark framing arch has been changed for a sunlit patch in the background. The new background helps balance the composition. The way the feather is silhouetted by the second child's hair gives more depth to this version. The outline of the second child's head feels as if it has been squished a bit as if the painter felt uncomfortable extending it beyond the picture plane. I suspect someone copied Leyster's painting and made major changes in an attempt to adjust the composition.

Cats Treated Poorly

The Netherlands in the 1600s was not a safe place and time for cats. For centuries people in Europe had associated cats with the devil. Torment and killing cats was considered acceptable. Upper classes at this time were welcoming cats into their homes. But public games involving killing a cat trapped inside a barrel were still common.

I'd prefer the man be gently patting the kitten instead of pulling its ear, but this is my favorite painting by Leyster. The restrained palette, the brush strokes, the man's expression are all so well handled. The kitten's face balances the man’s. Notice how the kitten's features are painted loosely so that they don’t compete with the focus on the man's face.

In this painting by Leyster, a ruddy-cheeked man holds a kitten. The man is wealthy enough to afford a feather the cap he wears at a jaunty tilt. If you're familiar with cat body language, you can tell this kitten isn’t happy... probably because the man is pulling its left ear!

What does this painting say about the sitter? It's doubtful that the kitten in his arms is a treasured pet. In this power dynamic, the man definitely has the upper hand. Everything about him speaks of confidence and control.

Leyster is best known for her genre paintings. The ordinary people she painted were shown living everyday life. She wasn't just trying to capture a moment in time though. By positioning her sitters in certain ways and including meaningful objects, she overlayed her paintings with additional meaning.

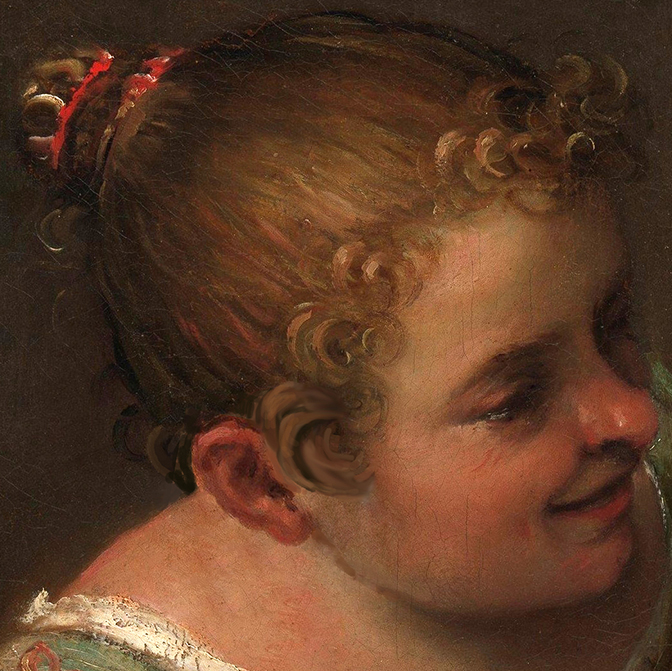

This figures in this painting of two children, an eel, and a kitten draws the viewer's eye around in a circle. The greatest contrast of light and dark is the boy's face and the straight edge fold of his hat. That guides the viewer to what he is holding behind the girl: an eel. From his impish expression, you can guess that he is about to wave the eel in the unsuspecting girl's face.

The girl has her right hand raised with the index finger extended, as if she's about to raise a point or explain something. "Let me tell you something important," she seems to be saying. But she isn't making eye contact with the viewer, she's looking off to the side in a rather sneaky manner... because her other hand is ready to pull the kitten's tail!

The kitten is the only one making eye contact with the viewer. His gaze is like a period at the end of a sentence. If the boy scares the girl with the eel, she will pull the kitten's tail. The kitten will then scratch the boy holding him. Consequences matter!

Unhappy Cats a Frequent Subject

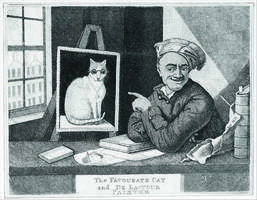

Judith Leyster was certainly not the only painter to show people tormenting cats. Her own husband painted at least one version. Several years ago I came across a version of children tormenting cats in this painting by Annibale Carracci, who predated Leyster's by several decades. The theme is similar to her painting of the two children with the eel and the kitten.

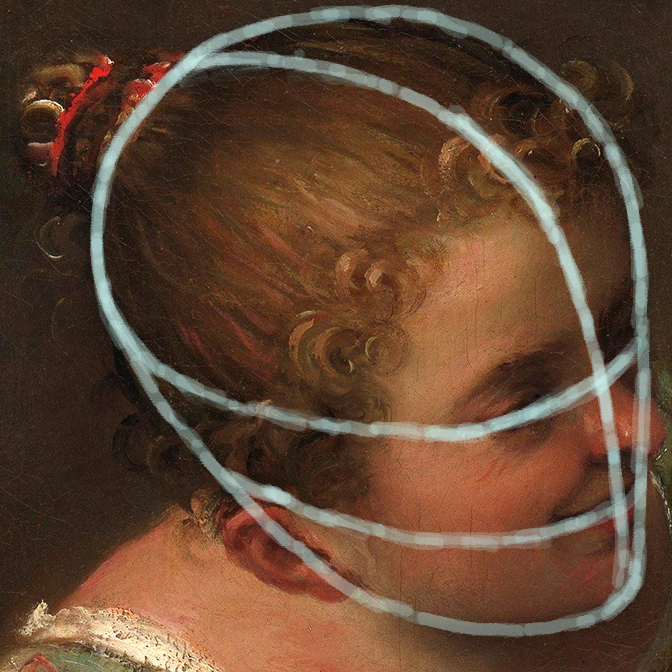

When Annibale Carracci painted this, his point wasn't necessarily that children are cruel, but that people in general should think before acting. At least one of these children will likely get pinched by the crayfish or scratched by the cat. The composition is based on a triangle. Our eyes are drawn from the girl to the crayfish her brother holds, to the unhappy cat, and back to the girl again. Not quite drawn as well is the girl's ear positioned under,instead of above, her jawline. That ear is probably why I remember this painting.

Generally, the top of a person's ears line up with their eyes, and the bottoms line up with their lips. Here's a rough mock-up showing how the girl's ear might be better positioned. Carracci is a far better painter than most of us will ever be, but it is fun to notice details like this.