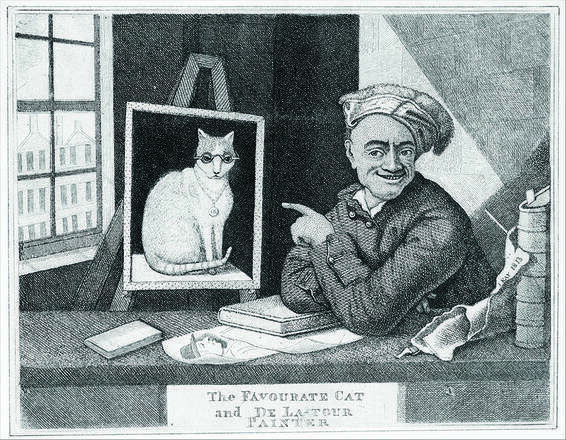

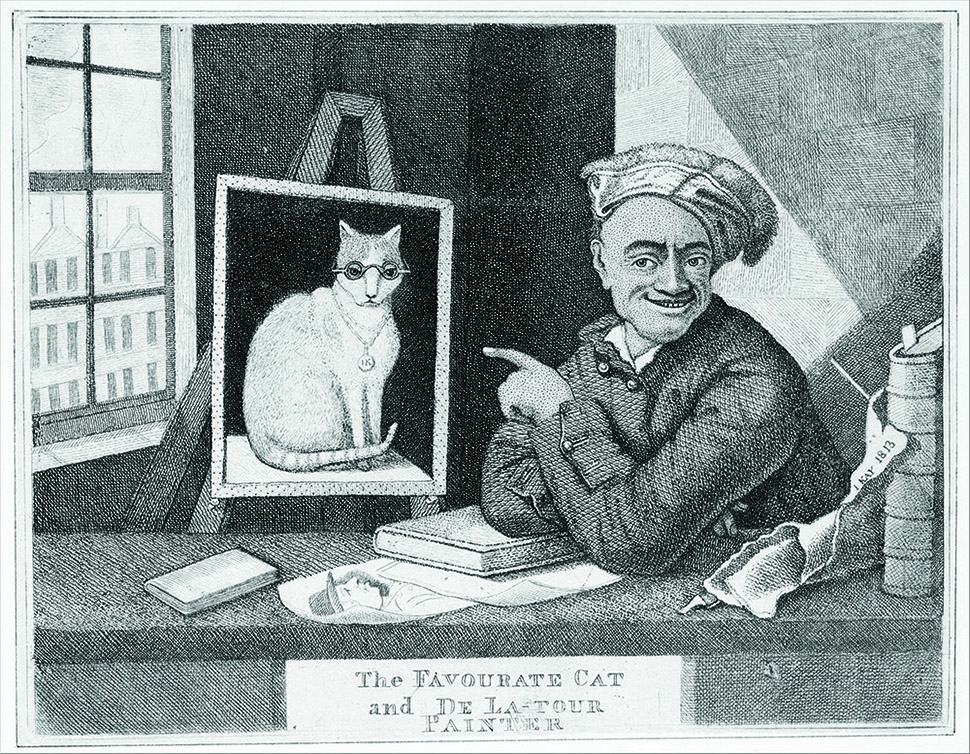

The Favourite Cat and De La-Tour Painter by John Kay

https://www.zazzle.com/store/catartists?rf=238405805277786293

https://www.zazzle.com/store/catartists?rf=238405805277786293

In many of the engravings (John Kay’s included) the figure of de La Tour is flopped to be pointed in the other direction. When printing with an engraving, the printed image will be reversed from what is engraved on the plate. John Kay engraved this in 1813: de La Tour had died in 1788.

The subject of this etching, Maurice Quentin de La Tour, was a prolific French pastel painter and philanthropist. During his lifetime, owning animals as pets versus work animals became more popular. Before this it was considered wasteful to keep an animal around unless it earned its keep, guarding the house or catching mice.

“Favorite” was an early term for “pet.” Although nowadays we might interpret a person’s “favorite cat” to mean the favorite cat of many owned by the person, back then it probably just meant a “pet cat.”

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Painter of French Nobility

Perhaps in part because they tend to be more cooperative when it comes to posing, dogs were the more popular pet in paintings at this time. Even so, I could only find a few dogs in the backgrounds of de La Tour’s paintings, and not a single cat.

So why does this engraving show de La Tour posing with a cat painting?

If you look closely at the engraving above you will see that the date it was made—1813–was long after de La Tour had died. It was common for engravers to copy painted artworks. In this case the engraver, the Scottish artist John Kay, reinterpreted one of the many self-portraits de La Tour painted of himself.

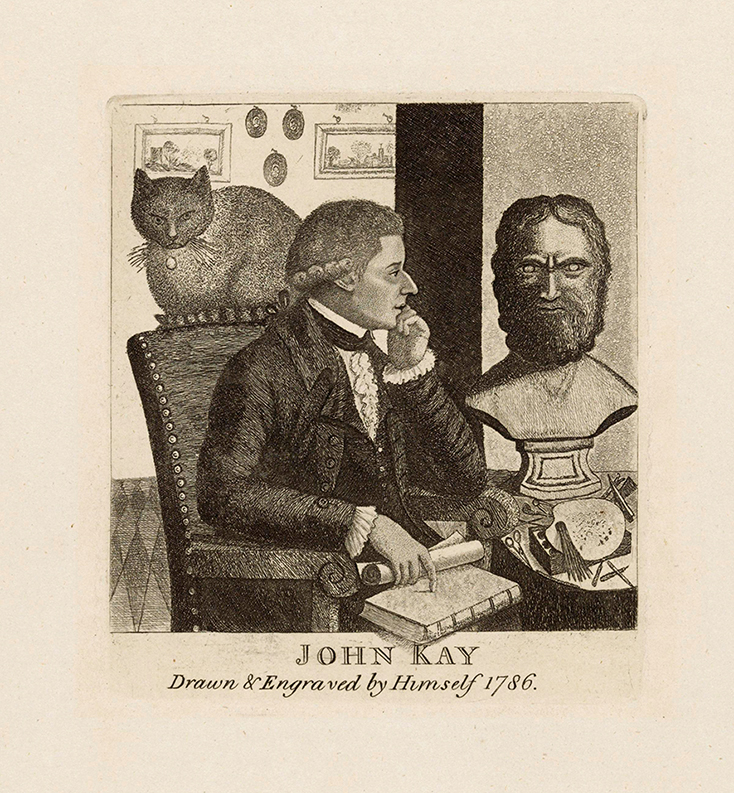

John Kay, Self-taught Artist

An accomplished self-taught miniature painter, John Kay (1742-1826) originally trained as a barber-surgeon. For centuries before, barbers not only cut hair, but also performed surgery and dentistry. If that seems odd, consider that barbers were better-skilled with knives and razors than most anyone else. During Kay’s lifetime, the rules were changed so that barber- surgeons were no longer allowed to do surgery if they also cut hair.

Once set up in Edinburgh, John Kay was employed by different genteel families. He became indispensable to the one local Scottish noble in particular who encouraged Kay’s artistic growth and left him financial support upon his death.

Besides painting watercolor miniatures, Kay began to publish his etchings and engravings. Some were of historical figures. Most were caricatures of famous people or politicians of Edinburgh. He exaggerated their proportions and expressions. Or he put them in amusing situations, such as his etching of a local musician waving his cane as he conducts the braying of three donkeys. Some victims of his wit threatened to sue him: others bought his artwork so that they could destroy it. Even so, it’s estimated he put out over 900 engravings during his lifetime.

De La Tour's Famous Self-portrait

Although there was a forty-year period when de La Tour and John Kay were both alive, it is exceedingly unlikely their paths ever crossed. Yet John Kay drew his caricature of de La Tour twenty-five years after the pastelist’s death.

Of his many self-portraits, the one showing de La Tour as an older man in a floppy hat became the Enlightenment’s equivalent of a meme.

One of the first copies was a copy within a copy by de La Tour’s student Marie Suzanne Roslin (Giroust). Her painting shows herself sharpening a pastel, ready to begin work on her charcoal sketch on the easel while de La Tour’s self-portrait hangs at the right as reference.

It was common enough for engravers to copy paintings. But something about de La Tour’s pointing finger encouraged the copyists to add their own interpretations.

What was de La Tour pointing at? In many interpretations, the rounded window was enlarged and its sill flattened to give space to add the vague outlines of studio equipment inside. Now de La Tour seemed to be pointing to his easel, to explain that he was an artist. In at least one version, a nude model in a suggestive position was added so that de La Tour appears to leer at her. (de La Tour is known for his portraits of his wealthy patrons, not nudes or mythological scenes that would include nudes).

By the time John Kay got around to his caricature, de La Tour’s self- portrait was easily recognized.

A Tabby Cat Wearing Eyeglasses

But why did Kay include a cat in his version? And why a common tabby cat, not an Angora or Chartreux as were popular in France at the time? Did Kay somehow know that de La Tour liked cats? Although the reputation of cats was improving—some people even saw them as symbols of political freedom—many still regarded them as unlucky, unrestrained, or evil beings.

John Kay's favorite cat and the statue of the philosopher share an impressive frowning brow. The engraving shows miniatures hanging on the back wall and his brushes sit on the table next to him.

>As one of John Kay's own self-portraits show, he himself did like cats. His biography included a tongue-in-cheek boast that his tabby cat was "the largest it is believed in Scotland."

John Kay engraved this particular self-portrait 27 years before his version of de La Tour's. The tabby in John Kay's self-portrait is wearing a bell. But the tabby in his engraving of de La Tour is wearing a long chain with a medallion engraved with his own initials: JK.

Is the tabby John Kay's caricature of himself? Is he poking fun at his own artistic endeavors compared to the talented mastery of de La Tour?

Another hint may be the eyeglasses the cat is wearing. At first I thought that the glasses were a nod to the superior intelligence of cats, or that the white stripes around tabby eyes reminded John Kay of spectacles. But then another thought came. I suspect that when you make your living painting miniatures and etching small works, you would rely on a pair of eyeglasses to put in the finer details.

Rachel Armington